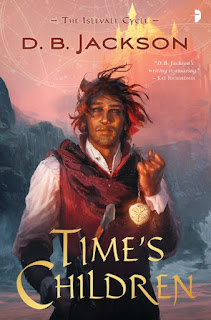

The Islevale Cycle. The book has just been released by Angry Robot Books. The second volume, Time’s Demon, will be released in May 2019.

The Islevale Cycle. The book has just been released by Angry Robot Books. The second volume, Time’s Demon, will be released in May 2019.As D.B. Jackson, he also writes the Thieftaker Chronicles, a historical urban fantasy set in pre-Revolutionary Boston. As David B. Coe, he is the author of the Crawford Award-winning LonTobyn Chronicle, which he has recently reissued, as well as the critically acclaimed Winds of the Forelands quintet and Blood of the Southlands trilogy. He wrote the novelization of Ridley Scott’s movie, Robin Hood, and, most recently, The Case Files of Justis Fearsson, a contemporary urban fantasy.

He is also currently working on a tie-in project with the History Channel. Coe has a Ph.D. in U.S. history from Stanford University. His books have been translated into a dozen languages.

He and his family live on the Cumberland Plateau. When he’s not writing he likes to hike, play guitar, and stalk the perfect image with his camera.

Jackson applied the Page 69 Test to Time’s Children and reported the following:

When I first tried the page 69 test on Time’s Children I was a little disappointed. I hoped the page would have some cool action sequence, or a moment of magic or time travel (which plays a huge role in the book and series). Instead, I found a page that really isn’t representative of the rest of the book. It consists largely of dialogue between my antagonist, and the Autarch for whom he works.Learn more about the book and author at D. B. Jackson's website and blog.

But as I thought about it more, I realized that one exchange between them feeds into a central subplot of the book, and an important element of what I like to do with all my villains. Something you need to know: Time travel in my world exacts a heavy cost. For every day or month or year my Walkers go back in time, they age that much. And then they age that much again returning to their own time. So if I am twenty and I go back a year, I arrive in the body of a twenty-one-year-old, and when I return to my rightful time, I am twenty-two. Here, the autarch speaks of sending one of his other assassins back fourteen years to pursue my protagonist. This assassin happens to be the wife of my point of view character for the scene.

Here’s the exchange:

[The autarch says] “Make your arrangements. But I want plans in place in case this doesn’t work. The woman is prepared to follow this lad back in time?”Orzili may be my assassin, my “bad guy,” but I go out of my way to humanize him, to make his emotions and fears and needs (and those of Lenna, the Walker to whom he is wed) as powerful and relatable as those of my hero. Here, we see him daring to challenge perhaps the most powerful person in my world, who is also his employer. He knows he shouldn’t, but he dreads seeing his love’s life spent for the sake of Pemin’s bloodlust. If she is sent back after “the lad” and then returns to their shared time, she will have aged twenty-eight years. Their life together will never be the same.

The woman. “You mean my wife?” Orzili said, none too wisely.

Pemin stared, his expression icy. “I mean my Walker.”

I want my readers rooting for my heroes. I want them hoping that Orzili and Lenna will fail. But I also want the failure of my anti-heroes to carry an emotional cost. None of this should be easy. None of it should be drawn in black and white. Shades of gray. That’s what I’m after. And in this case, on page 69, I am beginning to set up the core emotional struggle of a key character. That he is my villain makes it no less crucial to my narrative.

D.B. Jackson is also David B. Coe, the award-winning author of a dozen fantasy novels.

The Page 69 Test: Thieftaker.

Writers Read: D.B. Jackson.

--Marshal Zeringue