write children’s books, and work for a literary agency before going to teach English in India and Thailand. Swan earned her MA from Teacher’s College at Columbia University and began teaching in New York’s public school system in 2008.

write children’s books, and work for a literary agency before going to teach English in India and Thailand. Swan earned her MA from Teacher’s College at Columbia University and began teaching in New York’s public school system in 2008.

While teaching full-time, Swan attended the MFA program at the New School and graduated with a degree in fiction. Her work has been published in various journals, including Portland Review, Atticus Review, The South Carolina Review, and Inkwell Journal, and her stories have been nominated for the Pushcart Prize and Best of the Net.

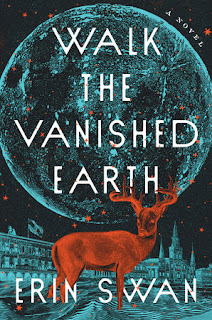

Swan applied the Page 69 Test to Walk the Vanished Earth, her first novel, and reported the following:

From page 69:Visit Erin Swan's website.Speaking is not easy, but Carson is patient. When she grows tired of talking, he has her draw. Today he takes two soft objects from a room with a door.I think the Page 69 Test absolutely works for my book.

“Try these,” he says.

They have the fur and faces of animals, but their eyes are white with black dots in the center, like no creature she has seen. She spends time gazing into these eyes, but can see nothing.

“You can play with them,” he suggests. “Move them around. What would they do? What would they say to each other?”

She tilts her head to the side. Animals cannot speak in the way he means.

“Or you can just hold them.” He gets up and returns to the narrow room. She sees the two objects he brings back and she gets up. She does a quick turn from wall to wall, and then returns to her seat.

“No,” she says, as clearly as she can. She shakes her head. One object is a woman. The other is a man. The woman wears a dress and her eyes are buttons. The man wears something blue from shoulders to ankles. On his feet are two big boots. They are pointed at the tips, not square, but she knows them.

“No,” she repeats, and stands up.

This page reveals a pivotal moment for my character Bea, a pregnant 12-year-old who has attempted to walk north from New Mexico only to end up on the children’s ward of a mental institution in Kansas City. Having suffered significant trauma, Bea struggles with both speech and memory. She often interrupts her own attempts at speaking with the harsh bark of a deer and sometimes cannot form words at all. Although she has dim recollections of her former life, she cannot remember precisely what set her on the road north. In this scene, her psychiatrist Dr. Carson is using play therapy to trigger her memories. He hopes that if she can access them, he’ll be able to treat her more effectively. His first attempt is a failure. Bea doesn’t recognize the stuffed forms as real animals and so is unable to engage with them. The male and female dolls he hands her, however, strike a chord. In them, Bea recognizes two significant figures from her life. She isn’t ready yet to face these memories, and so she refuses, saying No clearly, as Dr. Carson has taught her.

Walk the Vanished Earth features several characters within the same family line, but I see Bea as the most central. The baby she is carrying will be Paul, who is destined to build a floating city in New Orleans when massive hurricanes decimate coastlines across the globe. Later, he will help design the Red Star Project, which will send his granddaughter Penelope to Mars. On page 69, Bea is poised to discover the truth of what was done to her and what she, in turn, did to others. This trauma will haunt her and will also haunt her descendants, both in literal dreams of a man walking through a desert and in the figurative dream of “making the world anew,” a dream that Bea’s father passed to her and which she will pass to Paul when they reunite years later.

In this scene on page 69, we see many threads that run throughout the book: family lineage, intergenerational trauma, resistance and the power of choice, the push and pull between the natural world and the human world. One might say that from this moment, all else unfurls.

Q&A with Erin Swan.

--Marshal Zeringue