book publisher W.W. Norton & Company and The New Yorker, in the magazine’s fiction and literary department. She was the associate editor on the New York Review Books Classics series and the fiction and literary editor at Playboy magazine and later at Esquire. She’s also worked in digital publishing, as an executive editor at e-singles publisher Byliner and as an acquiring editor and content creator for Scribd Originals. She has been an adjunct professor at the Columbia University MFA writing program and a MacDowell and Yaddo fellow. She lives between New York and New Hampshire.

book publisher W.W. Norton & Company and The New Yorker, in the magazine’s fiction and literary department. She was the associate editor on the New York Review Books Classics series and the fiction and literary editor at Playboy magazine and later at Esquire. She’s also worked in digital publishing, as an executive editor at e-singles publisher Byliner and as an acquiring editor and content creator for Scribd Originals. She has been an adjunct professor at the Columbia University MFA writing program and a MacDowell and Yaddo fellow. She lives between New York and New Hampshire.

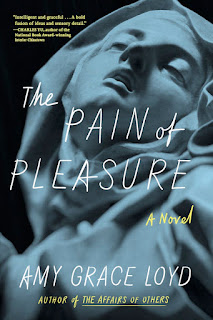

Loyd applied the Page 69 Test to her new novel, The Pain of Pleasure, and reported the following:

On page 69 of The Pain of Pleasure you’ll find one of the main characters, a neurologist, Dr. Louis Berger, is making a house call for one of his patients, Mrs. Adele Watson, a chronic migraine sufferer who’s having a bad episode. But she’s not just any patient, she’s his employer, the wealthy patron of the headache clinic he oversees, which is situated (for better and sometimes worse) in the basement of a church. Adele, a widow, also happens to be in love with the doctor and wants far more from him than medical attention, while the doctor does his very best to attend his professional duty to Adele and no more.Visit Amy Grace Loyd's website.

That page offers a really intimate look at so much that drives the novel — misaligned agendas and battles of will, how to cope with and solve physical and emotional pain and how very individualized and subjective this can be, the drama of unrequited love, and of course it captures how much human desire is at work in the story in all its aspects: unruly and irrepressible, ugly and beautiful.

On this page the doctor is intent on finding the right remedy for his patient’s pain — the mechanism of which, he knows, is unique to her — but his patient wants him to get into bed with her. “Lie with me,” Adele pleads with him. Who has the power? Adele? The doctor? Who or what is in charge? Is it Adele’s pain? Or her longing? Or is it the doctor’s duty and his resistance to Adele’s overtures? And can he resist her? Does he really want to?

He's made concessions to her that may have misled her, he admits here, by always coming when she calls, because he is enormously invested in solving the puzzle of her pain. When he injects her with an anti-nausea medicine, he lays a hand over the site to apply pressure. What kind of meaning does that take on when his patient has fallen for him, who even while incapacitated is reaching for him “as if moving through viscous water” and “grabb[ing] heavily for his wrist”?

It was important for me at a time when we’re reexamining gender and sexual dynamics to write a man who is trying, however imperfectly, to hold an ethical line —to do no harm per his physician’s oath, to be a good doctor and especially a good man. This scene previews what’s to come in the continued tugs of war not just between these two characters but also between Adele and Ruth, the nurse Adele enlists to spy on the doctor, between Adele and her son, and of course between the doctor and his missing patient, a young woman he wanted to love but his duty and its distortions got in the way. This page lays bare a human habit that seems terrifically hard for us to shake — our impulse to try to control one another, which invariably contributes to another habit, the habit of pain, creating it for ourselves over and over, as if we have no other choice.

--Marshal Zeringue