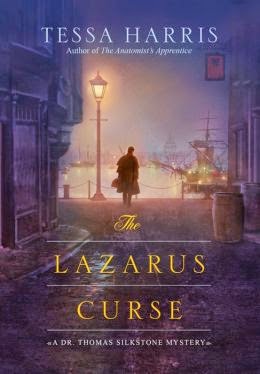

Harris applied the Page 69 Test to the new novel and reported the following:

Harris applied the Page 69 Test to the new novel and reported the following:From page 69:Visit Tessa Harris's website.Thomas edged forward on the small landing. “Then I shall certify the death,” he said, looking toward the open door of the attic room.My page 69 excerpt finds Dr Thomas Silkstone at the London home of a sugar merchant who owns vast estates in Jamaica. Samuel Carfax divides his time between the West Indies and England, accompanied on his travels by his vicious and cruel wife, Cordelia, and their house slave entourage. The irony is, of course, that slavery was not legal in England in the 18th century, but plantation owners were allowed to be accompanied by their slaves, who were often treated in a most barbaric manner. Moreover, such treatment seems to have gone unquestioned in ‘polite’ circles. After Thomas has treated Mr Carfax, he hears wailing from the servants’ quarters and finds a slave boy has recently died, seemingly of fever. Over the next two pages Thomas offers to write out the boy’s death certificate, even though he was sure the child’s body would, in all probability, be dumped in an unmarked grave. He also offers to treat Mistress Carfax’s slaves at no charge if another should fall ill, even though he knows she would never permit it. She cares for the dog mentioned in the passage more than her ‘Negroes’ and we later learn that while Cordelia Carfax’s dead pets all have headstones, her slaves do not.

Mistress Carfax’s back stiffened. “Is that really necessary, Dr. Silkstone? He was only a…” She broke off as she read Thomas’s disapproving expression.

“A slave, ma’am?” He finished her sentence for her.

There was little room to maneuver on the cramped landing and only a few inches separated them. The woman’s breaths came in short, sharp pants. She nodded and stuck out her chin defiantly, stiff-faced, as if her cheeks and lips had been starched. “Yes,” she said finally. “A slave.”

Thomas leaned closer to her and lowered his gaze to meet hers. Her eyes were as cold and unseeing as those of the fish in his laboratory. Flattening his lips in a smile, he began to shake his head. “The law may be ambiguous as to whether a slave is an animal or a human, but I would be failing in my duty as a physician if I did not examine the child.” He let his words linger on the air until the woman blinked and agreed with a sullen nod.

“Very well, Dr. Silkstone,” she muttered, letting Thomas pass into the room.

He walked in to find Venus comforting Phibbah, trying to still her sobs. Her long thin arms were wrapped ’round the girl, whose head was nestled on her shoulder.

“I am a physician,” he told her, walking toward the boy. As Venus nodded, Phibbah pulled away. She eyed Thomas suspiciously as he knelt down, took the child’s emaciated wrist, and felt for his pulse. There was none. Lifting his lids, Thomas looked at the boy’s pupils. They were fully dilated. He was satisfied that his short life had ebbed away.

“The fever?” he asked, lifting his gaze and looking at Venus. She simply nodded.

Pulling back the coarse sheet, he looked at the boy’s torso. His ribs showed through his brown skin like the veins of a leaf. He was evidently malnourished, thought Thomas, so that his guard was already down before the fever struck.

Mistress Carfax returned to the room, without the dog, and walked over to Thomas, fixing cold eyes on the corpse.

What this random pull from the text shows is the contrast between the acceptance of slavery in English society and the enlightened attitude of our hero, Thomas Silkstone. Appalled by the hypocrisy of the time that sees dogs treated better than humans, he finds himself battling against dark forces in the depraved world of sorcery, slavery and murder to order. It’s also a world where money, politics and power all hold sway, and where then, as now, such notions are rightfully challenged by a few good men.

My Book, The Movie: The Devil's Breath.

--Marshal Zeringue